Foodways in 1910

This article, written by the Montana Heritage Project, details the eating and cooking habits in early American Society. It’s a fascinating look into how stoves came into existence, and offers insight into why many people still prefer to use cookstoves.

When visiting cultures that are new to us, a close look at how people eat takes us directly into the core issues of who they are. The more we understand their eating habits and practices, the more we understand their political, religious, economic, and social systems. We can begin to understand them as people, seeing why they made many of the choices they made.

Foodways include all the details about what and how people eat, where their food comes from, who prepares it, what rituals and activities go along with getting it, preparing it, serving it, and eating it. As you come to understand a people’s foodways, you come to understand their world.

Though it’s natural to begin by comparing their foodways to our own, it’s important to remember that they could not see us. To see things as they saw them, we need to think about the realities they themselves compared their lives to. For the people who inhabited the America of 1910, two realities shaped their thinking: their own recent past and the world of the future. They were keenly aware that the world was changing rapidly, and the possibilities presented to them by new manufacturing and transportation systems were thrust before them constantly by advertisers in national magazines and mail order catalogs.

Their Past: Most people in 1910 cooked on stoves, but for some the hearth was still a living memory. We still use the word “hearth” to refer to the warm center of a home. We might say that a mother who kept her home a welcoming place for a child gone away to school “kept the hearth fires burning.” But those of us who’ve grown up in houses with central heating need to use our imaginations to get a sense of how people in the past experienced their hearths.

Most American homes did not have stoves until well into the 19th century, so cooking was done in an open hearth, using heavy iron pots and pans suspended from iron hooks and bars or placed on three-legged trivets to lift them above the fires. Pots and pans were made mostly of heavy cast iron. Along with long-handled spatulas and spoons, most kitchens featured long-handled gridirons to broil meat and toasting forks to hold slices of bread.

Though some women used Dutch ovens and some had clay ovens built outside, until after the Civil War when stoves with ovens became more common, people ate pancakes more often than bread. Because bread was hard to bake at home, most towns had bakeries. Bread was often the only prepared food that could be bought in town.

To keep a hearth fire going required constant attention and lots of work. The cook knelt by open flames where cinders flew from unscreened fires, lifting and moving heavy pots, and reaching into the heat to stir or turn cooking food. Burns were common injuries, and women’s long dresses sometimes caught fire.

To get firewood, most people needed to saw down trees and then chop them up and haul the wood home. Carrying wood to fill the large woodboxes that customarily sat beside the hearth was an endless chore. And as the fire burned, ashes needed to be hauled back outside.

The hardest work, though, was keeping water in the house. People typically hauled buckets of water into the house 5 to 10 times a day. A lucky family had a well near the house, though such wells never seemed close enough. Others hauled water from creeks and springs, often a good distance from the house. In winter, they had to break ice or thaw hand pumps.

One woman whose well was 60 yards from her kitchen estimated that during the 41 years she lived in her house she hauled water up the hill to her kitchen over 6,000 miles. Of course, sinks did not have drains, so water also needed to be hauled out again when it was dirty. So did the contents of chamber pots, which were used before indoor toilets. Many poor people lived without indoor plumbing well into the 20th century.

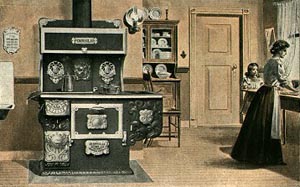

By 1900, nearly all houses had cooking stoves. To people who remembered hearth cooking, these appliances were wonderful. They were easier to use and safer than hearth fires (though the amount of work they took may still seem astonishing to people like ourselves, accustomed to gas and electric ranges).

Coal became more and more popular through the 19th century as railroads brought it from distant mines and as forests near cities were cut down. By 1900 it had replaced wood as the main source of home energy. More and more, the household was becoming dependent on spending money in the market rather than upon family members’ labor. People switched to coal because it took less work than wood. It was a more concentrated energy source, so less of it needed to be hauled. Also, it burned longer and more evenly. Cooking was easier and tending the fire took less time.

Still, coal stoves were far from trouble-free. A study of coal stoves done in 1899 found that during a six-day period, “twenty minutes were spent in sifting ashes, fifteen minutes in carrying coal, and two hours and nine minutes on blacking the stove to keep it from rusting.” During those six days, “292 pounds of new coal were put in the stove…, 27 pounds sifted out of the ashes, and more than 14 pounds of kindling” were hauled. To keep one fire burning through the winter required 3-4 tons of coal. Needless to say, you wouldn’t fire up the stove simply to heat a cup of hot chocolate.

All day long women tended their stoves, adding fuel, adjusting dampers to control heat to the oven or water tank, stirring the pot of beans, or hauling water to keep the hot water tank full. Many houses only had one heated room, and during the winter much of the house went unused as people huddled near the the kitchen stove. People lived very close to each other, without much privacy.

At the beginning of the 20th century, only two appliances were common in the kitchen: the stove and the gear-driven egg beater. Although plenty of devices had been patented throughout the 19th century to make kitchen work easier and more convenient, nobody bothered to manufacture most of them until ways to mass produce and transport them to consumers were developed. The main way of marketing to households in the 19th century was the traveling saleman, with his pack or wagon of patent medicines and novelties.

Their Future: Though the drudgery of keeping house was commented on often by women from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was often a note of optimism about the miracles the future held. Things were getting better than they had been in the not-so-distant past, and people expected things to keep improving. The World’s Fair at St. Louis in 1904 featured several huge buildings dedicated to progress: the Palace of Electricity, the Palace of Varied Industry, Machinery Hall and others.

A newspaper calculated the total engine capacity at the Fair was “about 56,000 horse-power.” Furthermore, since “an engine horse-power is really one-fifth greater than the average power of the ordinary draught-horse, the total engine capacity can be made to equal the power of something more than sixty-seven thousand horses-or a line of horses one hundred and twenty-eight miles long.” It all seemed miraculous, and it was leading to a steady stream of better machines for the kitchen. Most people felt confident that railroads and factories would use the ingenuity of manufacturers and scientists to continue making life better.

In 1900, Americans had celebrated the nation’s centennial, occupied the entire continent, and become more important on the world stage by winning the Spanish-American War. People were optimistic. The railroad system had more miles of track than all the countries in Europe combined. Electricity was beginning to find its way into houses: light bulbs, water heaters, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, electric irons, and portable power tools. Almost a million households were connected to telephone lines.

What They Ate: At the beginning of the 20th century, not much food came in the small packages we are used to. Though large corporations had begun creating national brand names– Campbell’s soup, Borden’s canned milk, Quaker Oats, and Gold Medal flour– most of the food in general stores was shipped in bulk, usually packed in barrels weighing 200 pounds or more. A shopper handed a list to a clerk who then retrieved the items from behind the counter. The general store had bulk items such as flour, coffee, sugar, tea, and green coffee beans that needed to be roasted and ground at home.

If you wanted fresh butter, eggs or vegetables, you would try the farmers market where local farmers sold their excess. If you wanted bread you went to the bakery. If you wanted meat you went to the butcher. If you bought chickens, you might take them home unplucked or even still alive. Grocery shopping was slow and the customer had few choices.

For the most part, shopping had little to do with eating. Only a small percentage of most people’s food was bought. Mostly, they produced it or grew it themselves. Even people in town grew large gardens and kept chickens (and sometimes a cow).

The diet of many people tended toward things easily grown and preserved. Salted pork was a mainstay because pigs were easy to raise and the meat kept well. Many dishes featured corn: soaked and turned into hominy, ground and mixed with rye or wheat for bread, or served on the cob in season. Butter and cheese were easier to store than milk, and hand churns were a common kitchen utensil. Turnips, pumpkins, and beans were popular vegetables because they kept well. Green beans were sun dried into “leather britches.”

Mass produced glass jars were not available until after1900, so few households did home canning before then. Food was preserved either by drying or by storage in a cool root cellar. Before refrigeration or access to ice for ice boxes, most houses had cellars. Stoneware jars (with rocks placed on the lids to keep them closed) might be filled with pickles, molasses, apple butter and pickled meats. Carrots were packed in moist sand in the basement, and potatoes were buried under straw. The cellar was used to store butter and cheese, as well as eggs. Since animal fat was important–used for making soap, candles and shortening–after butchering cellars were often piled with stands of lard. Mass produced glass jars available in the early 1920s were much cheaper than hand-blown jars, and these, along with pressure cookers in the 1930s, led to wide-spread home canning. Industrious women filled their cellar shelves with jars of green beans, tomatoes, fruits, peas, corn, relishes and pickles.

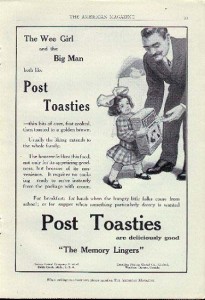

The creation of nationally marketed brand names accelerated quickly between 1900 and 1910, and such foods became staples rather than luxuries. Kelloggs and the National Biscuit Company began replacing tins with recently invented cardboard boxes, which provided a cheap container that could easily bear printed advertising. General stores began to stock more and more boxes, tins and cans, rather than barrels of bulk goods. Corporations eagerly sought ways to use new machines and a national railroad system to sell to the home market by taking on much of the work of growing and preparing food.

A Changing World: Changes rippled throughout society, with many small things contributing to much larger changes. Many 19th century women never handled money or were consulted on financial decisions. Though of course some did manage the household finances, others had their economic lives dominated by their husbands. Even their personal belongings, such as jewelry, legally belonged to their husbands.

As more products for the “women’s sphere”–not just for cooking but also for laundry, sewing, and cleaning–became available, women began making more financial decisions. This, along with their growing freedom from constant drudgery, helped change the way they thought about their possibilities in life. By 1910, the drive to give women the vote was well underway.

The changing food economy was also part of a larger change in the way people thought about money and buying things. As people got more and more of what they needed at stores rather than from near-subsistence farms, they began to think of themselves more and more as workers and consumers. Mail order houses, department stores, and chain stores made buying and selling more and more impersonal, and the advertising industry grew rapidly as businesses studied the arts of creating a desire for purchases. The creation of a distinctive American culture as a dizzying mix of media hype and nonstop consuming was underway.

The world of 1910 was a world in transition. Many people still lived as their ancestors had 200 years before in the colonies. Others, particularly the wealthy in cities, were living in a new world of technological miracles, with indoor plumbing, electricity, telephones, and automobiles.

For many who came to Montana, the urge to make progress in their personal lives was strong, even as they struggled to get the bare essentials of life. Homesteaders were taking a bold and frightening step to create better lives for themselves. They came from all over the world, and they were mostly poor.

Settlers on the Great Plains and in the Rocky Mountains in the 1910s often commented on the difficulty of getting enough food. They usually brought flour, sugar, salt, and jerky with them, but most also purchased canned goods and flour and salt at local stores, though few had any spare cash.

A homesteader in Saskatchewan noted that “We did not have very much to eat. In fact I believe we would have starved to death had it not been for the neighbors… [who] gave us rutabagas and a trap so that we could catch rabbits at night. Mother took the fat off the rabbits to fry our potatoes in and rabbit was our only meat since we did not have a gun to shoot anything with. I used to get so hungry I would eat grass.”

The main trend in American foodways through the 19th century and early 20th century was for more and more of the work of growing and preparing food to be exported from the household to large corporations. This led to far less work for ordinary people, as well as a better selection of food and better nutrition. It also led to less time spent together in family and community settings preparing food.

Some people feel that today the trend of putting corporations rather than families in charge of our foodways has continued too far, with many people not only bringing mass-produced foods into their homes, but leaving their homes to take most of their meals in corporate-created settings at fast food restaurants. A recent book, Fast Food Nation, focuses on this trend.

– By Michael Umphrey

Courtesy of The Montana Heritage Project, 2004.